Omar Alakhras: Helping people is part of my character

Estonian Refugee Council's Jordan branch Head of Office, Omar Alakhras, sheds light on how he first started to provide help to Syrian refugees, why he supports women rights and last but not least, how he ended up working for Estonian non-profit organization. Interview by Hille Hanso, Estonian Refugee Council, Middle East Project Coordinator.

Tell us a little about how you came to work with the refugees and in the humanitarian sector?

I started in 2011, almost ten years ago now. I first started with Relief International (RI) as an emergency response coordinator. They found my CV interesting because I am a local living in Jordanian– Syrian border region in ar Ramtha city, which is the closest Jordanian town to Syria. I speak several languages (Arabic, German, English, some French and Italian) - so they thought I could be useful. Besides, my grandmother is from Syria, so I am personally connected to the crisis.

Dara’a region, where the Syrian revolution started, is close to ar Ramtha, so of course, people fled across the border and found refuge there. Please describe the early days of the crisis?

I was directly involved in helping the first families who arrived from Dara’a governorate. Fleeing people stayed in ar Ramtha in three or four buildings where we visited them, where we sent them aid, tried to coordinate what was needed. I was leading the efforts to help, collected things to them, collected donations. The government was not involved yet; there were no controlled entering points on the border; those were created only in 2013. On the border, you could clearly see the bombarding because some villages are less than a kilometer away. Those fleeing were crossing the border, and we ended up picking them up with our cars, took them to hospitals when needed, or sent them the available housing. Jordanians rushed to help - they were on the border, waiting with first aid kits, doctors volunteered to treat them. Many locals in ar Ramtha divided their houses into two and left the other half to Syrian families. Syrians kept coming – we saw them appearing from the olive yards, from valleys, some injured, some traumatized, carrying their belongings. We rushed to them – just as any human being would do to help. So we started activities there with Relief International, and I became their senior program officer.

A training for starting enterprises, organized by Estonian Refugee Council.

A training for starting enterprises, organized by Estonian Refugee Council.

It turned out to be a colossal displacement of millions of people, and at the beginning, no one could estimate how massive this crisis is going to be[i]. How has all this influenced life in Jordan?

For one, Jordan is one of the most water-scarce countries in the world[ii], where typically, a cup of drinking water is shared by three people. So, of course, the whole infrastructure, water and waste management, and supply of goods etc., were severely affected. In 2014 and 2015, there were significant tensions between Syrian and Jordanian workers because international organizations supported refugees by giving them shelter and other types of aid. They started working for peanuts - when a local wants to be paid 10 JOD, then the refugee will do the same work for 2 JOD because their very basic needs were covered. But Jordanians did not get free medical service or shelter, or food aid, and the cost of living is very high in Jordan. So they could not work for the same fees, whereas business owners and employers took an opportunity of cheap labour, creating considerable tensions in the employment sector. Therefore, simple workers became resentful of having Syrians around. This became a reason why the government removed the people from cities, and the Zaatari camp was set up.[iii]

Meanwhile, the tensions also spread just based on ethnic background - even Syrians who had lived in Jordan before the crisis, who were not refugees, were targeted.

After the initial chaos, what happened?

Around 2015 and 2016, we could move from emergency management to the phase of development. Then we started to support small and medium enterprises, capacity building, etc. At this stage, the government of Jordan wanted to set a rule that part of the beneficiaries of the international aid has to be vulnerable Jordanians. The UN Refugee Agency pushed for 70:30, but this was rejected by the government, who claimed that the crisis had affected Jordanians equally. Keep in mind that unemployment was high before Syrians came, and they hardly got any aid to manage. So they pushed for 50:50. The phase of development gave a chance for Jordanians also to gain from the development aid and grants, skills development, training courses, etc.

Did you join Estonian Refugee Council because we are also focusing on livelihoods?

Yes, I applied around three years ago. I felt I have good experience in this area. Some programming was delayed because it took time to get registered in Jordan, but we have overcome that too.

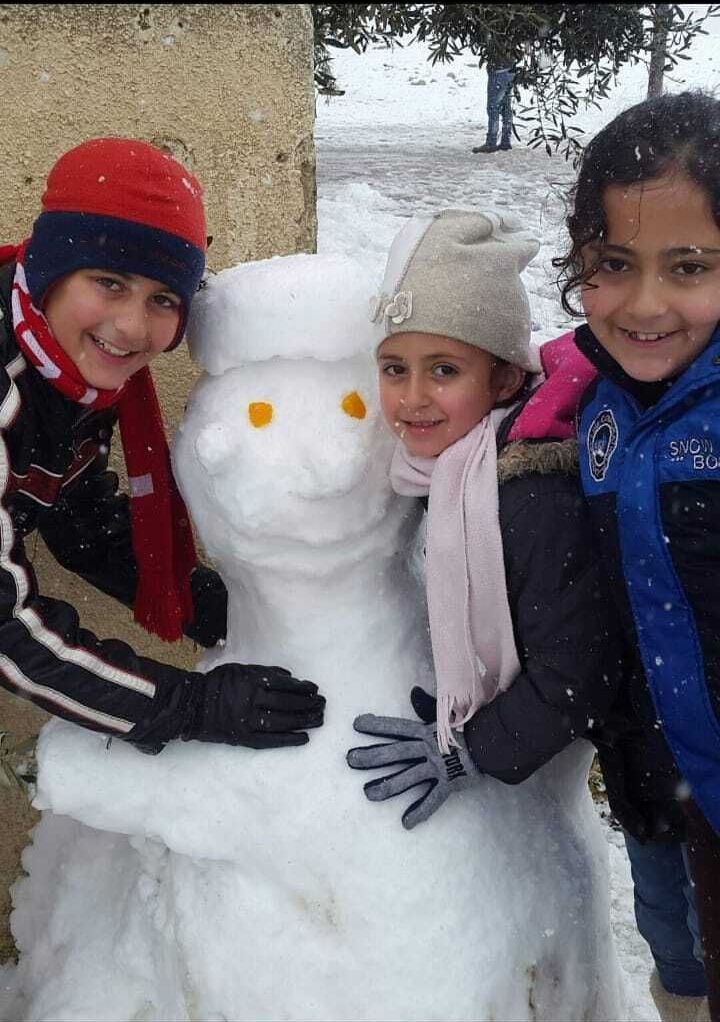

Omar with one of his daughters.

Omar with one of his daughters.

What did you know about Estonia before?

A lot, actually. I have lived briefly in Kyiv, where I worked on importing trucks they produce to Jordan. I know that region and the Baltic region pretty well. I started following developments there since the 1990s.

What are the most memorable work-related moments during the years you have been a part of our team?

When people get help, their gratitude is moving. However, not all the people who participate in our business development training get our small and medium enterprises starting grants. They have to compete for them, although actually, 99% are worthy of getting them. The sad side of our work is that we can’t provide grants to everyone. The most challenging part is to tell a person – you passed the training, you did well, you developed your business plan, but you will not receive the grant, you were not selected. They are really keen to get into starting businesses, and the disappointment is significant because they all need something immediate.

But when we deliver the good news that they have been chosen, we give them the equipment or items they applied for – those moments are unforgettable. The whole family will gather; they are so thankful. Kids are excited, and you see big smiles on their faces. When we interview them months later and get feedback that they have started or upgraded their business and family’s income has grown, it is so rewarding. I can see that these people have directly benefitted from Estonian Refugee Council’s grants.

Omar with his daughter.

Omar with his daughter.

One of Estonian Refugee Council’s principle of aid is gender equality. You have also been very keen on the empowerment of women. Can you explain your views, since you come from a region which is generally pretty patriarchal?

First of all, low income is a big problem, and when only one family member is working, it is not sustainable, and they will face big problems. Also, it is an unfair burden on men to be a sole breadwinner. It puts them under a lot of pressure. I think women deserve a chance to develop their skills, and all family members are equal, so they all should contribute. It is true that in more conservative villages, it is not acceptable that women leave homes for work on the market or elsewhere, or they don’t want to leave their homes – there are ways they can work from then.

That’s why I am especially keen on engaging people from the villages, and we make sure that at least half of the beneficiaries are women, so they’d get more opportunities, and these views would change. Life in the cities is more open-minded.

...but traditionalists say woman’s place is at home. If you disagree, then they will bring in the religion and argue that modesty requires that they are not out and about.

Yes, this is what they say, and it is my job to change that. Everyone understands the rational argument about the families being stronger economically if also women can earn income.

And it is women’s right to take roles in their communities, in their society. There is nothing revolutionary about it. Mind you, it is not like we are “giving” women rights for the first time in history. They are reclaiming the rights they have historically had.

I believe women in Jordan should be able to behave like those in Europe. That is why we must target rural areas. I have two daughters – what if one of them finds a husband in a village? I don’t want her to be stranded because of these customs. My older daughter is called Julia, which is not a Muslim name. We named her as such to give her full freedom of being related to any religion. I want them to have a choice to do whatever they please in life, and I am delighted that she is interested in the humanitarian sector- she is asking me many questions about my work. They have asked me if I would agree if they went to study abroad. I told them I am 100% behind their decisions.

That is why I don’t particularly appreciate talking about “empowering women” – they are already empowered. They have enough abilities, skills and are totally equipped to go ahead. Only the tradition is blocking them.

Omar says he would always support his children' s decisions.

Omar says he would always support his children' s decisions.

Islamic feminism is claiming that women played a significant role and filled many public positions in society at the time of the Prophet. They say that it is unIslamic to restrict women’s rights.

Yes, in history, women’s involvement was common; women were more equal to men, not like now. These days, religion is used to justifying to lock the girls at home, and I find this outrageous. I know people whose girls come to Irbid town for the first time for shopping, they are astonished by city life, and this is very sad. I am not a religious person, though, and it is hard for me to reason based on religious principles.

But it sure is hard to understand how in the 21st century, we have a life in Amman which is modern and then ar Ramtha or villages, which are so backward. On a more positive note, we see the all-time highest number of women in the universities. So things are moving in the right direction. Although I have to add, many don’t educate their daughters because they want them to have a career, but they aim to marry them off better. So when a girl gets a degree, and she’d like to get a job, the father might reject it. Yet, it is better if they have an education. It is a start; they will demand more in the future. Nevertheless, I find it ridiculous to educate a girl without her having any prospect of using her skills to earn income for her herself and her family.

What are the biggest challenges in our work?

There is a significant need; our funds are small. We can only target small and medium enterprises and limited numbers. Our investment is small, but the number of applications is enormous! We get thousands of applicants word-to-mouth, without even advertising our grants.

Second, we are helping Syrians to get work permits in Jordan, and the number of those budgeted to get it is under 30. But the need for work permits is vast and especially women need them as only 15% of work permit holders are women. We must achieve more.

You are a very compassionate person. Where do you get your values? How do you motivate yourself?

I like to help people. It is my personality, a part of my character. Icould work in a Ministry or bank, etc., but to me, the effects of our interventions, the relieved smile on people’s faces, is essential. And it excites me to give new skills to people, this is good for the whole society. Especially kids – they have to have opportunities and rights, or we will face similar problems in the future.

Does the Estonian Refugee Council change people’s lives in Jordan?

It does. Even though small scale, because our grants are small, but now that we are registered, I will do my best to get us participating in larger projects and co-operations. And if you think of it – even if we target 50 people, it will have a multiplying effect - because indirectly, all of them support five more. So we have 250 people benefitting in what we do - no one can say this not significant!

[i] Jordanian government estimates there are around 1.4 millin displaced Syrians in Jordan.

[ii] 3rd most water scarce in the world, its renewable water supply meets about half of Jordan’s population's water needs.

[iii] Zaatari camp is the biggest refugee camp in Jordan, which did contain up to 100 000 people. The camp is as big as Estonia’s 2nd largest city, Tartu.